Description

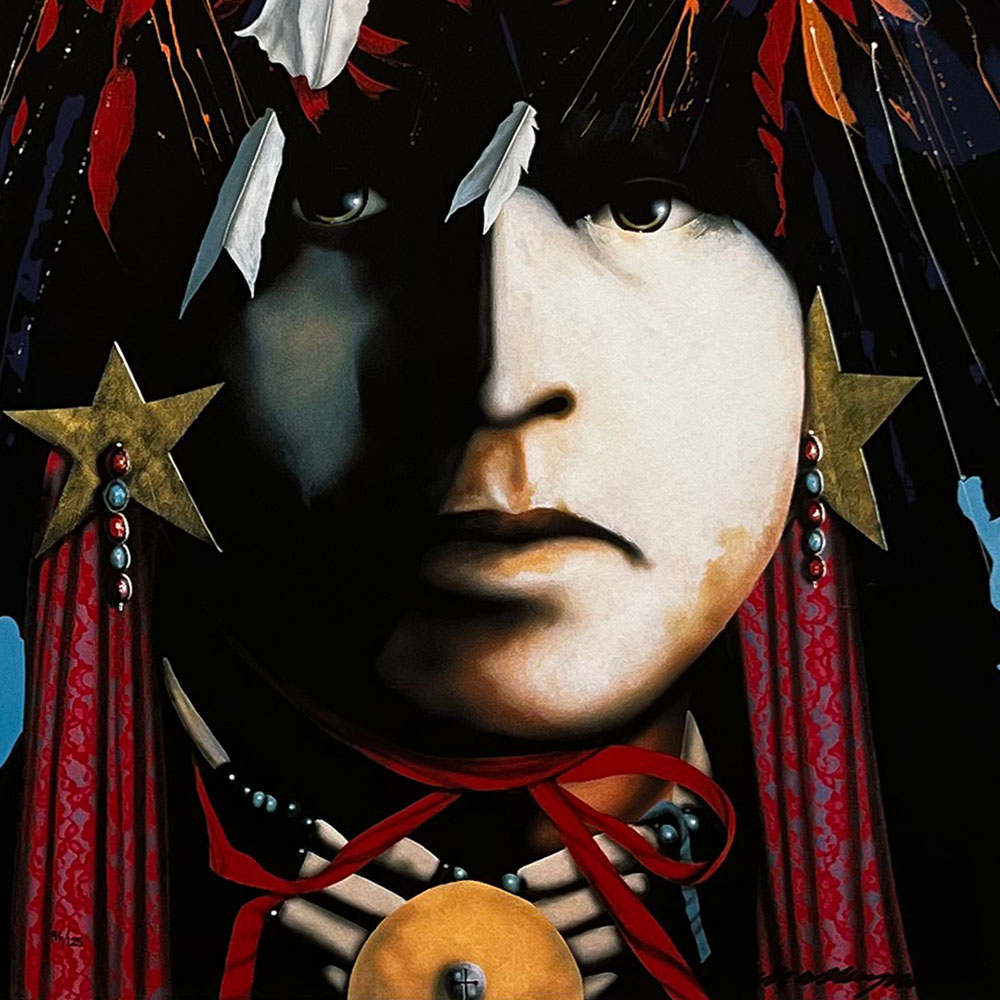

Pure, perfect, powerful: these are the words which first come to mind in experiencing the art of Bonita Barlow: pure for its simplicity and brilliant clarity; perfect for the inherent perfection in the close harmony and unity of its universal forms; powerful for its extraordinary impact on the consciousness of the observer. After a closer observation, a still more significant experience becomes apparent; that of the great beauty of these paintings, a beauty made mystical by the critical effect of immaterial light. Light in art has always had spiritual associations. In some of Barlow’s latest paintings, this light actually coalesces into spirit-forms, ghost images, which could be considered souls, now released from the material confines of the geometric manner of the majority of her works. It is light which transforms into a sacred space, any gallery in which the paintings of Bonita Barlow are exhibited.

While the scale difference would make it seem unlikely, the closest kinship in art to Barlow’s geometric paintings would be with the great pyramids of Egypt. The pyramids when first built were faced with smooth, polished stone, the upper part covered in gold. The pyramid design, a pure geometric form, was contrived to catch and articulate, in a grand way, the light of the divine sun as it moved across the sky. It is probably no coincidence that the only example of an art comparable to Barlow’s in the modern world would be Donald Judd’s display of aluminum cubes, installed nearby at the Chinati Foundation in Marfa. To stand in Judd’s space with its hundred cubes, carefully placed in terms of the light coming from the windows, is like standing within the sacred space of the Cathedral of Chartres.

As is the case with the great pyramids of Egypt, Judd’s cubes, and the interior of Chartres, the sheer magic of Barlow’s paintings is in how they function in light, a light that absolutely demands our attention. These paintings reach aggressively out into the space around them, literally capturing and manipulating our movements when we discover that, as we pass before them, they change in appearance depending upon the angle of the light in relationship to our position. The emotional content of each painting is transformed as our location changes, and we realize, with some awe, that the work of art is itself alive and moving with us. This light is not an illusion as in normal paintings, but actual light reflected from glass particles in the pigment, bound to the light sources in the room. Thus the entire surrounding space, including the observer, is pulled into the work of art. Nothing like it has ever happened before in the art of painting. Yet how classically modern these paintings are on the one hand, in their apparent continuation of the modern machine aesthetic, as in the paintings of Piet Mondrian and Josef Albers, or the sculptures of Donald Judd. But how absolutely unique they are in the way their appearance shifts before our eyes. Bonita Barlow’s paintings, in the manipulation of actual light, provide an aesthetic experience never seen before in the history of art.